Introduction

Many functions are provided by JavaScript host environments that allow you to schedule asynchronous actions. In other words, actions that we initiate now, but they finish later. Take a look at the function loadScript(src), that loads a script with the given src:

function loadScript(src) {

// creates a <script> tag and append it to the page

// this causes the script with given src to start loading and run when complete

let script = document.createElement('script');

script.src = src;

document.head.append(script);

}

function loadScript(src) {

// creates a <script> tag and append it to the page

// this causes the script with given src to start loading and run when complete

let script = document.createElement('script');

script.src = src;

document.head.append(script);

}

Let’s say we need to use the new script as soon as it loads. It declares new functions, and we want to run them. But if we do that immediately after the loadScript(…) call, that wouldn’t work:

loadScript('/my/script.js'); // the script has "function newFunction() {…}"

newFunction(); // no such function!

loadScript('/my/script.js'); // the script has "function newFunction() {…}"

newFunction(); // no such function!

Naturally, the browser probably didn’t have time to load the script. As of now, the loadScript function doesn’t provide a way to track the load completion. The script loads and eventually runs, that’s all. But we’d like to know when it happens, to use new functions and variables from that script.

Let’s add a callback function as a second argument to loadScript that should execute when the script loads:

function loadScript(src, callback) {

let script = document.createElement('script');

script.src = src;

script.onload = () => callback(script);

document.head.append(script);

}

function loadScript(src, callback) {

let script = document.createElement('script');

script.src = src;

script.onload = () => callback(script);

document.head.append(script);

}

That’s the idea: the second argument is a function (usually anonymous) that runs when the action is completed.

Callback in callback

How can we load two scripts sequentially: the first one, and then the second one after it? The natural solution would be to put the second loadScript call inside the callback, like this:

loadScript('/my/script.js', function(script) {

alert(`Cool, the ${script.src} is loaded, let's load one more`);

loadScript('/my/script2.js', function(script) {

alert(`Cool, the second script is loaded`);

});

});

loadScript('/my/script.js', function(script) {

alert(`Cool, the ${script.src} is loaded, let's load one more`);

loadScript('/my/script2.js', function(script) {

alert(`Cool, the second script is loaded`);

});

});

What if we want one more script…? So, every new action is inside a callback. That’s fine for few actions, but not good for many, so we’ll see other variants soon.

Handling errors

In the above examples we didn’t consider errors. What if the script loading fails? Our callback should be able to react on that.

loadScript('/my/script.js', function(error, script) {

if (error) {

// handle error

} else {

// script loaded successfully

}

});

loadScript('/my/script.js', function(error, script) {

if (error) {

// handle error

} else {

// script loaded successfully

}

});

The convention is:

- The first argument of the callback is reserved for an error if it occurs. Then callback(err) is called.

- The second argument (and the next ones if needed) are for the successful result. Then callback(null, result1, result2…) is called.

So the single callback function is used both for reporting errors and passing back results.

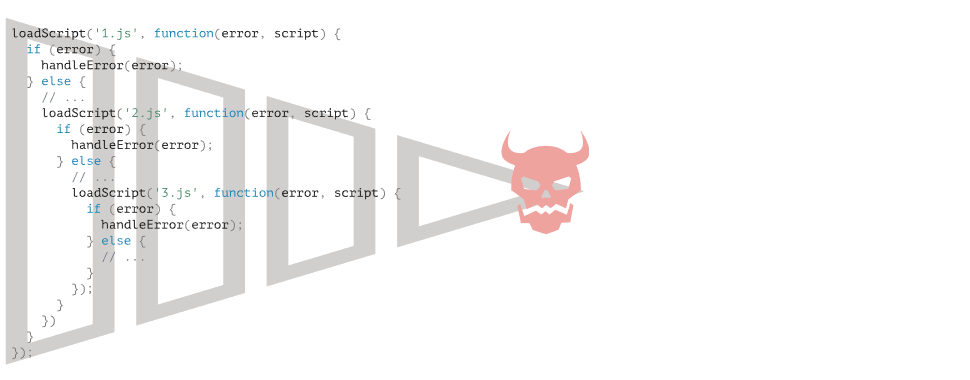

Pyramid of Doom

At first glance, it looks like a viable approach to asynchronous coding. And indeed it is. For one or maybe two nested calls it looks fine.

But for multiple asynchronous actions that follow one after another, we’ll have code like this:

In the code above:

- We load 1.js, then if there’s no error…

- We load 2.js, then if there’s no error…

- We load 3.js, then if there’s no error – do something else (*).

As calls become more nested, the code becomes deeper and increasingly more difficult to manage, especially if we have real code instead of … that may include more loops, conditional statements and so on.

That’s sometimes called “callback hell” or “pyramid of doom.”

Promise

Imagine a real-life analogy for things we often have in programming:

- A “producing code” that does something and takes time. For instance, some code that loads the data over a network.

- A “consuming code” that wants the result of the “producing code” once it’s ready. Many functions may need that result.

- A promise is a special JavaScript object that links the “producing code” and the “consuming code” together. In terms of our analogy: this is the “subscription list”. The “producing code” takes whatever time it needs to produce the promised result, and the “promise” makes that result available to all of the subscribed code when it’s ready.

The constructor syntax for a promise object is:

let promise = new Promise(function(resolve, reject) {

// executor (the producing code, "singer")

});

let promise = new Promise(function(resolve, reject) {

// executor (the producing code, "singer")

});

The function passed to new Promise is called the executor. When new Promise is created, the executor runs automatically. It contains the producing code which should eventually produce the result.

Its arguments resolve and reject are callbacks provided by JavaScript itself. Our code is only inside the executor. When the executor obtains the result, be it soon or late, doesn’t matter, it should call one of these callbacks:

- resolve(value) — if the job is finished successfully, with result value.

- reject(error) — if an error has occurred, error is the error object.

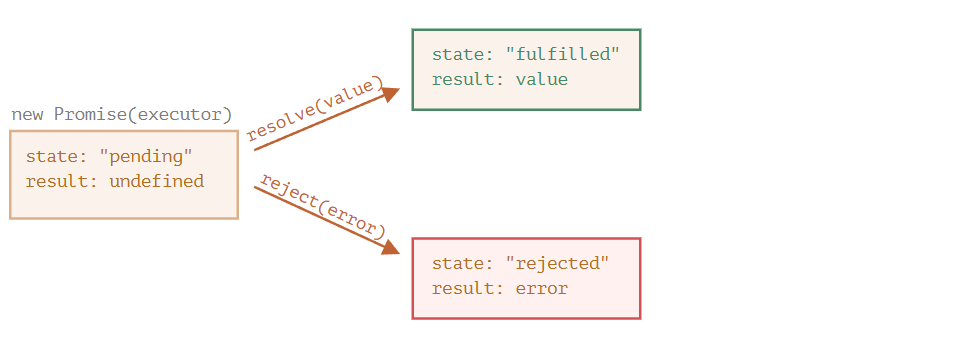

So to summarize: the executor runs automatically and attempts to perform a job. When it is finished with the attempt, it calls resolve if it was successful or reject if there was an error.

The promise object returned by the new Promise constructor has these internal properties:

- state — initially

pending, then changes to eitherfulfilledwhen resolve is called orrejectedwhen reject is called. - result — initially

undefined, then changes tovaluewhen resolve(value) is called orerrorwhen reject(error) is called.

So the executor eventually moves promise to one of these states:

To summarize, the executor should perform a job (usually something that takes time) and then call resolve or reject to change the state of the corresponding promise object.

then, catch

Consuming functions can be registered (subscribed) using the methods .then and .catch.

then

The most important, fundamental one is .then. The syntax is:

promise.then(

function(result) { /* handle a successful result */ },

function(error) { /* handle an error */ }

);

promise.then(

function(result) { /* handle a successful result */ },

function(error) { /* handle an error */ }

);

The first argument of .then is a function that runs when the promise is resolved and receives the result. The second argument of .then is a function that runs when the promise is rejected and receives the error.

catch

If we’re interested only in errors, then we can use null as the first argument: .then(null, errorHandlingFunction). Or we can use .catch(errorHandlingFunction), which is exactly the same:

let promise = new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

setTimeout(() => reject(new Error("Whoops!")), 1000);

});

// .catch(f) is the same as promise.then(null, f)

promise.catch(alert); // shows "Error: Whoops!" after 1 second

let promise = new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

setTimeout(() => reject(new Error("Whoops!")), 1000);

});

// .catch(f) is the same as promise.then(null, f)

promise.catch(alert); // shows "Error: Whoops!" after 1 second

The call .catch(f) is a complete analog of .then(null, f), it’s just a shorthand.

finally

Just like there’s a finally clause in a regular try {…} catch {…}, there’s finally in promises. The idea of finally is to set up a handler for performing cleanup/finalizing after the previous operations are complete.

- A finally handler has no arguments. In finally we don’t know whether the promise is successful or not. That’s all right, as our task is usually to perform “general” finalizing procedures.

- A finally handler “passes through” the result or error to the next suitable handler.

- A finally handler also shouldn’t return anything. If it does, the returned value is silently ignored.

Promises Chaining

Now we have a sequence of asynchronous tasks to be performed one after another — for instance, loading scripts. How can we code it well? Promises provide a couple of recipes to do that. It looks like this:

new Promise(function(resolve, reject) {

setTimeout(() => resolve(1), 1000); // (*)

}).then(function(result) { // (**)

alert(result); // 1

return result * 2;

}).then(function(result) { // (***)

alert(result); // 2

return result * 2;

}).then(function(result) {

alert(result); // 4

return result * 2;

});

new Promise(function(resolve, reject) {

setTimeout(() => resolve(1), 1000); // (*)

}).then(function(result) { // (**)

alert(result); // 1

return result * 2;

}).then(function(result) { // (***)

alert(result); // 2

return result * 2;

}).then(function(result) {

alert(result); // 4

return result * 2;

});

The idea is that the result is passed through the chain of .then handlers. Here the flow is:

- The initial promise resolves in 1 second (*),

- Then the .then handler is called (**), which in turn creates a new promise (resolved with 2 value).

- The next then (***) gets the result of the previous one, processes it (doubles) and passes it to the next handler.

- …and so on.

As the result is passed along the chain of handlers, we can see a sequence of alert calls:

The whole thing works, because every call to a .then returns a new promise, so that we can call the next .then on it. When a handler returns a value, it becomes the result of that promise, so the next .then is called with it.